There is a deep seam that lies astride the history of European archaeology - on one side you have the hero-explorers, men and women who took impossibly romantic risks to unearth artifacts from remote sites which were then shipped off to European museums, far from the reach of the cultures that produced them. They wrote books about their adventures that blended the excitement of the exotic travelogue with deep knowledge of (and many problematic assumptions about) non-European ancient history. On the other side lie the scientific archaeologists, journeying to destinations just as remote, suffering hardships just as profound, but approaching their work in a thoroughly different spirit, one of curiosity and measurement instead of acquisition and adventure.

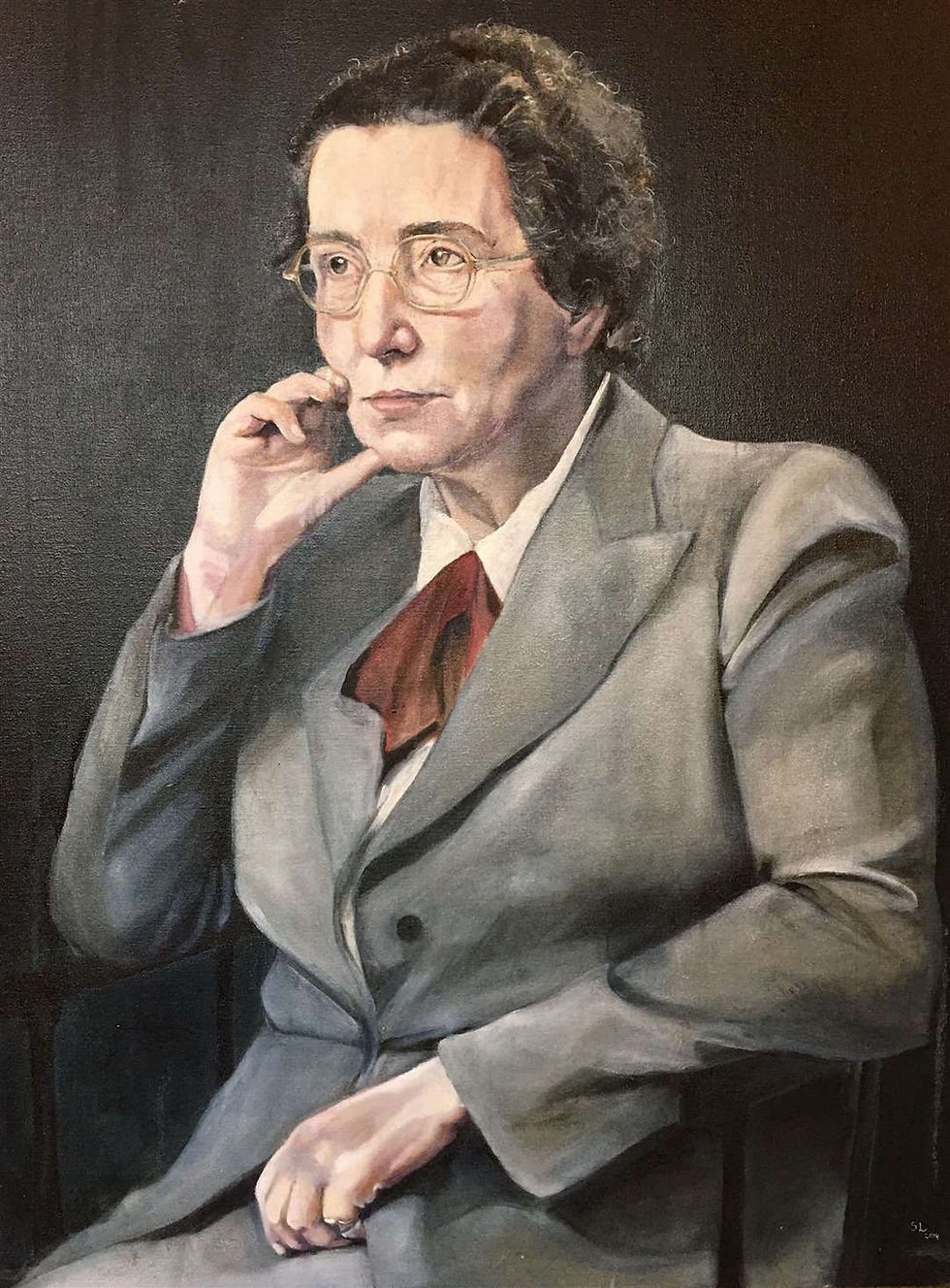

Locating that seam is tricky. Does it originate with the seriation methods developed by Flinders Petrie in the late 19th century, or perhaps the arrival of Wheeler's grid excavation system in the late 1920s or, as I believe, does it run squarely through the life of one individual, who married the use of new technologies with an approach to archaeological writing that forsook the sensational in favor of the verifiable so effectively that a return to old habits was impossible thereafter. Her name was Dorothy Garrod (1892-1968), and before she was nearly swallowed by her groundbreaking professorship at Cambridge she spent two decades accumulating major discoveries which demonstrated the objective power of a scientific approach to archaeological excavation and recording.

The daughter of Sir Archibald Garrod, a pioneer in the study of how biochemistry and inheritance intertwine to produce disease, and the grand-daughter of Sir Alfred Garrod, who was Physician Extraordinary to Queen Victoria, Dorothy was raised in an atmosphere of intense intellectual excellence. She and her three brothers were all seemingly destined for great things when World War I descended upon Europe to smother a generation in its cold fury. All three of Sir Archibald's sons were killed in the conflict, and Dorothy took it upon herself as a sacred duty to make up for their loss by her accomplishments.

The question then became, in what field was she to apply her drive and intellect? Devastated by the loss of her brothers (and possibly also her fiancé) in the war, she traveled to Malta to spend some time with her parents and determine a direction for her life. There, walking among the ruins, she found herself turned towards the problems and rewards of studying the deep human past, and when she returned to England she applied to Oxford's anthropology department in 1921 and by 1922 she was in France studying with the world authority on Stone Age paintings, Henri Edouard Prosper Breuil, known to history as Abbé Breuil. An innovative mentor, Breuil infused Garrod with a passion for prehistory, for untangling the complicated origins of humanity to discover how we came to be.

The two years she spent with Breuil were not only intellectually challenging, but spiritually profound. Garrod, who considered herself a deeply Christian individual, had to spend long, hard hours reconciling the clear antiquity of the civilizations she studied with the assertions of the Church as to the relative youth of the planet. The evidence of her senses and insights of her mind came hard against the dogmas of her youth and the emotional pull of belief, and in the end she managed a synthesis that allowed her to admit the great age of the world and the complicated evolution of humanity and thereby to continue her work.

Success was by no means guaranteed when she stepped onto the scene of her first archaeological dig at Gibraltar. The site at Devil's Tower was one recommended by Breuil as of potential promise, but for an individual who had moved from complete beginner to dig leader in the space of some short three years the potential for disaster was high. And yet, it was here, at Devil's Tower, that her career was made. She found the skull of a Neanderthal child, which she named Abel, painstakingly reconstructed it, and wrote up a report of her findings that was an absolute model of scientific rigor and restraint. The relative newcomer became an archaeological celebrity almost overnight, which allowed her to study a wider range of sites, but also threw her directly into the path of the century's greatest archaeological scandal.

The Glozel (or Glouzel) Affair pitted the archaeological establishment against a French farmer who had, while plowing his field, stumbled upon a chamber apparently filled with relics dating back to the Iron Age. A commission was established in 1927 to investigate the site, which included Garrod as England's youngest representative. Their conclusion, which for reasons we'll likely never know Garrod supported in her own separate statements, was that the overwhelming majority of the objects were modern forgeries. Using their combined authority, the commission crushed the amateur archaeologist and doctor who had been advocating the importance of the site and the farmer who had initially discovered it. Garrod was convinced she had done her part in uncovering a fraud, and the site was shut down. Decades later, however, spectrographic, thermoluminescent, and carbon-14 dating were employed on the Glozel artifacts, and showed that the bones, pottery, and glass in fact did date from the 4th through 13th centuries CE.

It was a messy moment in the history of archaeology which Garrod was well glad to have behind her as she turned her attention to the site that would transform her from momentary celebrity to one of the world's undisputed forces in the study of the prehistoric past. In 1929 she began her work at Wadi el-Mughara at Mount Carmel, a study that was to last a half decade and which would by its end result in the recovery of 87,000 stone tools, the unearthing of the first Neanderthal skeleton found outside of Europe, and the truly astounding discovery of five male, two female, and three child Neanderthal skeletons dating between 10,000 and 80,000 years old. Working patiently with her team of almost entirely women researchers and local workers, documenting rigorously, she filled in the prehistoric chronology with crucial finds that represented a true leap forward in how we told the story of our human past.

Success on such a scale could not be ignored by the establishment and so it was that when, in 1939, Dorothy Garrod submitted her application to become a professor at Cambridge, that bastion of male learning where no woman had yet been granted a full professorship, let alone in a field as male dominated as archaeology, she was selected for the position. As women all over the world celebrated this storming of the ramparts by a researcher of impeccable credentials, Garrod had to settle down to the reality of what she had won: the brilliant field leader would have to adapt to existence as a university lecturer and department organizer. The transition was not to be a happy one.

In trading the independence of the field for the prestige of the university, Garrod had struck an important blow for women academics everywhere, but at a terrible cost to herself. She was happiest, and her intellect shone most brightly, when out on a dig organizing people, establishing chronologies, and importing the latest technologies to improve the accuracy of her results. Her life at Cambridge, by contrast, was an endless circle of managing time-consuming department infighting, nursing fragile professional egos, and watching her students glaze over in boredom during the lectures that, she came to realize, she was not effective in delivering. All passion and concentration at an excavation, she was unilaterally described as a monotonous presence in the lecture hall, another example of the rule that brilliant minds do not always make for inspiring lecturers.

Nonetheless Garrod toughed it out for thirteen years until her retirement in 1952, interrupted only by a stint during the Second World War when she volunteered as a photographic analysis officer for the Auxiliary Air Force. Suffice to say, she took her retirement as soon as she was able and immediately lit out again for the field, to make up for lost time. She moved to France and began close collaborations with two other women archaeologists, Germaine Henri-Martin, and Suzanne Cassou de St. Mathurin. Together they were known as "The Three Graces" and their efforts included the discovery of Paleolithic art at Roc-aux-Sorciers in the early 1950s and the concentrated effort to preserve the Lebanese Ras el-Kelb cave that was slated for destruction to make way for two tunnels in 1959. Garrod spent her summers excavating and her winters in Paris where she lived together with St. Mathurin. She suffered a stroke while visiting Cambridge in 1968, and died several months thereafter in a nursing home at the age of seventy six.

Dorothy Garrod's drive to succeed was born from the example set by her family and the anguish of finding herself the lone survivor of a generation that had promised so much. She applied whatever scientific methods she could find to the production of iron-clad chronologies at dig sites spread throughout Europe and the Middle East, employing aerial reconnaissance and radiocarbon dating to accurately establish from all possible angles the validity of her findings. Her textbooks, dry and technical where those of her forebears had sparkled with flights of exotic prose, set the standard for how archaeology could redeem itself from its too-romantic past, and her example of self-sacrifice, of removing herself from the work she loved most in order to establish women as a presence in academic archaeology, is an example of tragic necessity to be remembered by all who have followed in her profound wake.

FURTHER READING:

Dorothy Garrod and the Progress of the Palaeolithic: Studies in the Prehistoric Archaeology of the Near East and Europe (1999) is a collection of pieces about different aspects of Garrod's career that is important, but hard to find and expensive when you do. I think a better entry point for most folks would probably be either Ofer Bar-Yosef and Jane Callender's Breaking Ground: Pioneering Women Archaeologists (2004) or Ladies of the Field: Early Women Archaeologists and their Search for Adventure (2010) by Amanda Adams. If you just can't wait, though, this article has some good detail on her life that isn't available in most of the English articles you find online. Sure, it's in German, but if you've stuck around with me for the last ten years of this column, you're probably used to me flinging Germans at you and have hopefully forgiven me for that predilection.

Comments