The Chemistry of Beauty: Hazel Bishop Betrayed.

- Dale DeBakcsy

- Aug 17, 2023

- 6 min read

Remember back when I said that botanists were the most under-respected members of the scientific community? Well, that's true until you consider a branch of science so underappreciated that many disdainfully refuse to even consider its practitioners as "real" scientists at all: cosmetic chemists.

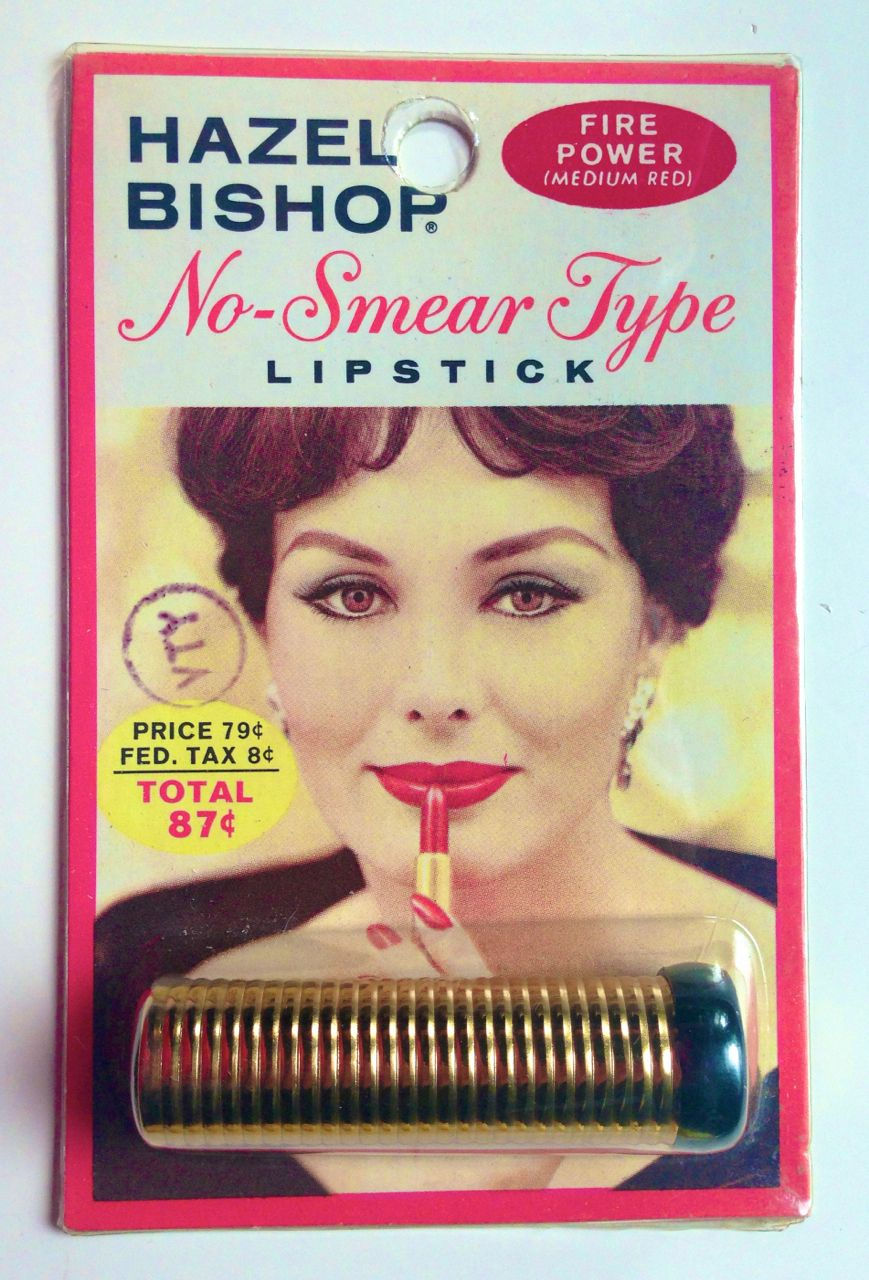

Either because they harness science in the name of practical aesthetics, or because their expertise lies in a field whose products are considered feminine and thus fundamentally lesser than those of other industries, the practitioners of cosmetic chemistry have been historically overlooked and too often forgotten. There is one person, however, whose name remains in our memory in spite of all that, the woman who invented the first mass-marketable indelible lipstick and founded a multi million dollar business on it: Hazel Bishop (1906-1998).

Lipstick is, chemically, a tricky thing. Considered from any angle, the odds are against it. It has to be long lasting but removable, vibrant but non-toxic, uniform under all conceivable temperatures, acidities, and moisture levels, and most importantly, it has to stay on you but not on anything else your lips happen to touch. Put together, that's an almost impossible chemical wish list with a long history of frustration leading up to Bishop's landmark efforts.

The first lipsticks were relatively simple: You take a species of beetle and crush it until you get a decent amount of carmine pigment out of its body. Add some zinc oxide to intensify the redness of the carmine, then mix it all into a wax and oil base. That will redden lips, but as it's just a pigment stuck in some wax, and it rubs off all the time, requiring constant re-application. It was a workable but pricey and often inconvenient solution to a problem.

Enter the dye. Instead of just coating your lips with something that approximated the color you wanted, why not instead just stain the actual tissue of the lips that color? Better yet, why not do both? By adding a water-soluble dye to the pigment-wax-oil base, cosmetic chemists were able to produce lipsticks that produced a vibrant outer pigment-based layer which rubbed off to reveal a dye-based layer of comparable color that would get you through the night (and, because it didn't come off, into the next morning as well, which was advertised as a "Wake Up Beautiful" positive rather than a "You've Just Stained Your Lips and Can't Undo It" negative).

The first synthetic dye, eosin, was developed in 1874 by Heinrich Caro. It is a neat derivative of fluorescein which has four bromines that, when they react with proteins containing either arginine or lysine (such as those in the skin tissue of your lips), produce a vibrant red color.

Perfect, problem solved, right?

Wellllll....

Eosin is water-soluble, which means that, if you want it to penetrate into lip tissue, you have to significantly moisten that lip tissue first. In moistening, some water will probably end up somewhere not precisely on your lips, and when you apply the eosin it will therefore stain that area as well, producing "feathering" and smearing that make your lips look like you've just been eating brains without particular regard for decorum. By the Twentieth Century, you therefore had two options: either a lipstick based on carmine pigments that came off all the time, or a pigment and eosin-based dye combination that, at the slightest mistake, would splotchily stain your whole mouth region.

The problem was the water, so chemists worked at producing a version of eosin that was water-insoluble, and eventually found it in the form of bromo acids, which would form the basis of Hazel Bishop's epochal lipstick line. These were synthetic dyes that you could dissolve in a solvent like stearic acid or castor oil, then add to the lipstick. A version of one of the first of these dyes, D & C Red No 21, is still in use today. But of course, you can't solve one problem without introducing another, and bromo acids, for all their promise of allowing accurate application, were highly corrosive, drying and damaging lip tissue in the long term.

Fixing that problem was Hazel Bishop's concern in 1950, but let's back up to see how she ended up at the forefront of an industry. She was born to practical, entrepreneur parents. Her father owned a small business and her mother managed it, instilling in Hazel an appreciation for advertising and self-sufficiency. Even with that push, her first ambition was to become a doctor, not a businesswoman. Unfortunately, she had the bad luck of graduating in 1929, when the American economy utterly collapsed. There was nothing for it but to take up a regular job during the day as a chemical assistant and to study chemistry at night to keep her knowledge base up to date. That situation persisted through the long and rough Thirties up until World War II.

Suddenly, with the men off to war, her chemical skill set was a hot commodity, and she easily found work at Standard Oil, where she worked on the problem of oil buildup on engine superchargers, and developed new gasolines for military aircraft. She was basically Rosie the Riveter, but with high efficiency petroleum combustibles of her own design in place of a drill.

I want that poster.

Her entrepreneurial upbringing stayed in the back of her head the whole time, and she started thinking about ways that she could turn her business sense and chemical skill to a profit in the post-war boom. She started experimenting at home with cosmetics, aiming to bring science and pragmatism to an industry often run by men who had no experience with the day-to-day hassle of cosmetic application. Where cosmetic magnates like Elizabeth Arden lived high lives of conspicuous luxury selling exotically named products that didn't last, Hazel Bishop lived with her mother and carried out experiments in the kitchen to produce a cosmetic that the average woman could depend on.

She decided on a pigment and dye combination, using bromo acids for the dye, but compensating for their corrosiveness by adding lanolin as a moisturizer. Over the course of three hundred experiments she tinkered with her mixture, balancing color purity against comfort and vibrancy against indelibility until she produced at last a lipstick that looked good and, properly applied, wouldn't come off on cigarettes or coffee cups or hunky Scotsmen.

She found a manufacturer and started selling locally. Her lipsticks bore names like "Pink" and "Red Orange" and "Dark Red" instead of the fanciful but not particularly instructive "Caribbean Dawn"-type titles of the traditional cosmetics industry. "Women want color information when they buy a lipstick, not a prose poem," she laconically commented. In spite of costing twice as much as a regular lipstick, her products flew off the shelves because of their unique properties. She hired an ace New York ad-man named Raymond Spector to launch Hazel Bishop, Inc. on a national scale in 1950, starting with a $1.5 million ad campaign that mixed sexual innuendo with consumer pragmatism to push Hazel Bishop's "kissable lipstick" into the national consciousness.

Soon, Bishop's lipsticks accounted for twenty-five percent of the industry and threatened Revlon itself, which launched a famous "lipstick war" to bury the upstart company. Spector and Bishop responded with intensive television advertising but, though the company was selling millions of dollars of products a year, it was also spending millions on its advertising budget, and the high-sales-but-low-profit-margin specter started doing its grim work.

But that wasn't Bishop's real problem. Her real problem was Spector, who exploited his original loose contract to direct company money towards his firm and began to buy up enough shares in the company to force Bishop herself out. In just four years, from 1950 to 1954, Bishop had invented a revolutionary new product, formed a massively successful business on its shoulders, reached the top of the industry, and been summarily thrown from her own company by a cunning charlatan. In her final sell-off of interest in the company, Bishop only received $310,000 during a year when the company's income was ten million dollars, and she was forbidden from using her own name in any future cosmetic ventures she might undertake.

Spector had taken her product, taken her company, and taken her very name.

Bishop tried to capture lightning again, using her chemical abilities to develop a leather cleaner, a perfume stick called "Perfemme", and a foot spray that relieved foot fatigue... somehow.... None of them took off with the same fire of her lipstick, however, and in 1962 she turned stock broker, harnessing her knowledge of business and marketing to thrust herself fearlessly into another male-dominated field at an age when most people are slouching down into retirement. In 1980, her old competitor, Revlon, acknowledged her multifarious gifts by giving her a chair position at its Cosmetics Marketing Institute.

She died in 1998, universally respected in the cosmetics and marketing industries.

Raymond Spector lost and regained control of Hazel Bishop, Inc. before devoting himself to a company that traded old RKO movies to television stations in exchange for free advertising slots, a scheme which went about as could be expected, and about as Spector deserved.

FURTHER READING:

There isn't a stand alone book about Hazel Bishop, it will come as little surprise. Virginia Drachman gives an interesting five pages of her book Enterprising Women: 250 Years of American Business to Bishop's story, focusing on the business end, while the chemistry involved is admirably covered over at CosmeticsAndSkin.com.

This piece was originally published as the 69th column in the Women in Science Series.

Comentários